Facing Anxiety: What is anxiety and how to manage it

- Francesca Zanardi

- Oct 17, 2024

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 30, 2025

" As I stand talking to the audience, I hope that my mind and voice will function properly...But then my heart start to pound, I feel pressure build up in my chest ...I can barely push the words out... My hands tremble. I start to sweat... I feel terrible and I think I will probably disgrace myself.."

Although sometimes overwhelming, these emotions have evolved to help us process information, signalling potential threats around us. Fear and anxiety, however, although adaptive emotions, can become excessive and interfere with our decision-making and daily lives.

In this article, we’ll explore the differences between fear and anxiety, dive into the symptoms of anxiety disorders, and uncover why we experience anxiety in the first place. Most importantly, we’ll look at practical strategies to help you regain control. By understanding the mechanisms behind anxiety, we can better equip ourselves to manage it. Scroll to the end for practical tips to manage anxiety. (Remember, if you're concerned about managing anxiety, it's important to seek advice from a medical professional)Difference between anxiety and fear

Anxiety and fear seem to be closely related, almost appearing to be the same sensation; however, although they overlap, they also differ. Whereas fear can be defined as a predictable response to an external stimulus, anxiety remains unpredictable. In other words, if you were known to be scared of spiders and I put in front of you a Tarantula, you would experience an instant of fear, however, If we were to explore a dark cave tomorrow, and the guide mentioned there was a spider inside, even though you couldn’t see it, you might start feeling anxious in anticipation of encountering the spider. This great analogy and parts of the following article were inspired by Alex Robinson, a Neuroscience professor at UCL (click here to hear the full speech). Thus, whereas fear is associated with automatic arousal necessary for a flight or fight response to an imminent threat, anxiety is more often associated with hypervigilance and muscle tension to future threat ideation.

Anxiety disorders symptoms

Anxiety, although adaptive, when it becomes excessive, can disrupt everyday life, impacting our decision-making. Awareness surrounding anxiety disorders and their symptoms is crucial specifically because recent research carried out by WHO [1] (World Health Organisation) estimated that in 2019, 301 million individuals suffered from a type of anxiety disorder, making it the most common mental health issue. Therefore, understanding such a disorder's psychological and neurobiological basis remains essential to better understanding how to treat it.

Although there are different types of anxiety disorders (general anxiety disorder, social anxiety, agoraphobia, separation anxiety, etc.) which can be differentiated by analysing the specific triggers, those disorders remain comorbid, sharing similar symptoms.

The DSM-5 [2] (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) identifies individuals with anxiety disorders as having excessive worry about a specific or broader situation for several consecutive months, with consequent avoidance of the possible triggering situations. Other symptoms may include irritability, extreme fatigue, trouble concentrating or experiencing "mind going blank", muscle tensions that can cause trembling and shaking, physical symptoms (including nausea, abdominal distress, diarrhea, sweating, heart palpitations), trouble sleeping, restlessness or feeling on edge and memory deficit. Anxiety disorders often start in childhood or adolescence, and girls are twice as likely to develop one.

But why do we experience anxiety?

Now that we've outlined the symptoms let’s explore what happens in the brain to cause anxiety. The brain is designed to help us anticipate potential dangers and prepare us to face them, which is why anxiety can be adaptive. However, in individuals with anxiety disorders, these mechanisms become overactive or dysregulated, leading to excessive or prolonged anxiety in response to both real and imagined threats. To understand why anxiety occurs, it's essential to look at how key brain structures contribute to this emotion.

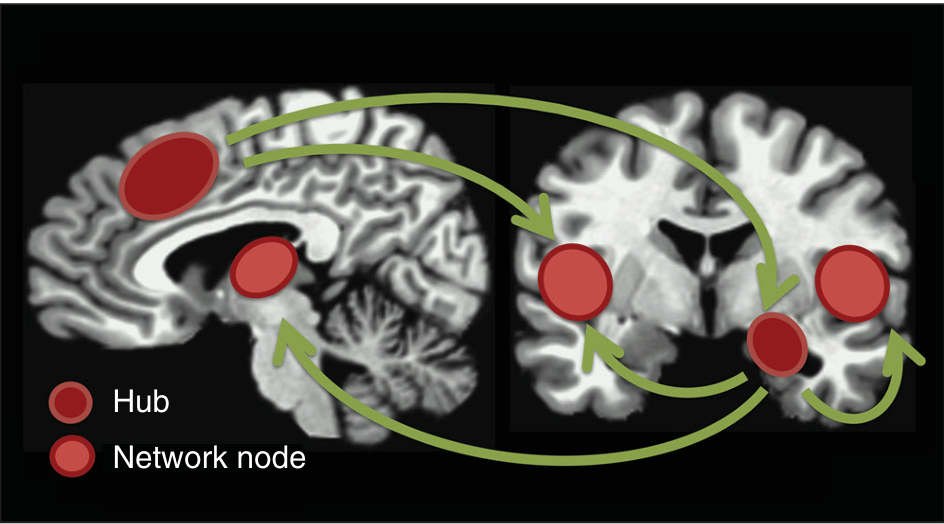

One of the central findings from recent research focuses on the role of the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC)–amygdala circuit. Under normal circumstances, this circuit activates during situations that require vigilance, such as anticipating potential dangers. The amygdala, known as the brain’s fear centre, detects threats, while the prefrontal cortex—especially the dmPFC—helps regulate these emotional responses by assessing and managing the threat. This mechanism is crucial for adaptive anxiety, allowing us to respond to danger appropriately. However, in anxiety disorders, this circuit remains persistently active even in the absence of direct threats.

This "aversive amplification circuit" stays chronically engaged, amplifying the perception of threat even in neutral situations, leading to excessive fear and worry[4]. This constant activation contributes to heightened and prolonged anxiety symptoms, reinforcing negative emotional responses.

In healthy individuals, the brain can distinguish between real and perceived threats, allowing the dmPFC-amygdala circuit to deactivate once the danger passes. However, in those with anxiety disorders, this deactivation does not occur properly. As a result, individuals are left in a continuous state of alertness, experiencing fear and worry even when there is no actual danger [3]. This chronic overactivation essentially traps individuals in a loop of constant threat detection, contributing to the distress and overwhelming feelings typical of anxiety disorders.

However, those findings detect brain circuit activation, which is extremely important for treatment research. But what do these findings actually tell us?

Importantly, these findings highlight the concept of affective bias—the tendency of emotions to influence decision-making and perception. In the context of anxiety, this manifests in several ways:

Attentional Bias: Individuals with anxiety often exhibit a heightened focus on threat-related stimuli, which can lead to an overwhelming sense of danger in everyday situations. This bias can cause individuals to overlook neutral or positive information, reinforcing their anxious state (Bar-Haim et al., 2007).

Memory Bias: Anxious individuals frequently struggle to recall neutral or positive experiences, instead favoring negative memories. This selective recall can create a distorted view of reality, contributing to feelings of helplessness and distress (Mathews & Mackintosh, 2000).

Sensitivity to Negative Information: Anxiety can heighten the perception of negative information, where individuals may interpret ambiguous situations as threatening. This sensitivity not only impacts emotional well-being but also affects decision-making processes (Eysenck et al., 2007).

The importance of Imagery: Imagery plays a significant role in anxiety by facilitating the internal visualization of feared scenarios or outcomes. This process can exacerbate anxiety, as vivid mental images of potential threats can trigger physiological responses associated with real danger (Hackmann et al., 2000). Moreover, maladaptive imagery often reinforces negative beliefs about oneself and the world, perpetuating anxiety symptoms (Holmes & Mathews, 2010). For instance, a person with social anxiety might imagine themselves failing in a social situation, leading to avoidance behaviors that further entrench their fears.

Such affective biases perpetuate a cycle of hypervigilance, where individuals remain constantly alert to potential threats, thereby intensifying their anxiety. Consequently, it becomes essential to develop strategies aimed at redirecting focus and reducing anxiety levels.

How to manage anxiety:

As noted, the brain activation patterns associated with anxiety create a circuit that keeps individuals hypervigilant, constantly monitoring their surroundings for threats. In situations of heightened anxiety, it’s crucial to redirect our attention toward something that does not increase arousal. Here’s some strategies:

Find a Boring Focus: Look for an object or scene that is particularly uninteresting. Focus on its color, shape, texture, or any detail that you can notice. This practice can help shift your attention away from anxiety-provoking stimuli and activate your parasympathetic nervous system.

Breathing Exercises: One effective technique involves imagining a square while breathing. Breathe in for a count of four along one side of the square, hold your breath for a count of two while moving to the next side, breathe out for a count of eight along the next side, and hold your breath again for a count of two. Repeat this process until you feel more relaxed. You may notice that your inhalations gradually lengthen, indicating optimal activation of your parasympathetic nervous system.

Progressive Muscle Relaxation: Another effective tip is progressive muscle relaxation (PMR). Start by tensing the muscles in your feet for a count of five, then release the tension while focusing on the sensation of relaxation. Gradually work your way up your body, tensing and relaxing each muscle group. This technique helps promote bodily awareness and can effectively reduce physical tension associated with anxiety.

Grounding Techniques: Engaging in grounding exercises can help bring your focus back to the present moment. Try the 5-4-3-2-1 technique: Identify five things you can see, four things you can touch, three things you can hear, two things you can smell, and one thing you can taste. This method can help anchor you in the here and now, distracting you from anxious thoughts.

Mindfulness Meditation: Practicing mindfulness meditation can help you become more aware of your thoughts and feelings without judgment. Set aside a few minutes each day to sit quietly, focus on your breath, and acknowledge any anxious thoughts that arise without trying to change them. This practice can increase your ability to cope with anxiety over time.

These methods are only temporary fixes that, with practice, could help manage anxiety. However, anxiety arises from underlying psychological issues, and if you are feeling that anxiety is taking over your daily life, it is always recommended to contact your doctor and/or consider seeking professional help from a mental health practitioner.

Further reading:

This is a great report on the lived experience of anxiety, what it is, and how to manage it: Living with Anxiety report | Mental Health Foundation

References:

World Health Organization: WHO. (2023, September 27). Anxiety disorders. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/anxiety-disorders#:~:text=In%202019%2C%20301%20million%20people%20in%20the%20world,people%20in%20need%20%2827.6%25%29%20receive%20any%20treatment%20%282%29.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Vytal, K. E., Overstreet, C., Charney, D. R., Robinson, O. J., & Grillon, C. (2014). Sustained anxiety increases amygdala–dorsomedial prefrontal coupling: a mechanism for maintaining an anxious state in healthy adults. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 39(5), 321–329. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.130145

Robinson, O. J., Krimsky, M., Lieberman, L., Allen, P., Vytal, K., & Grillon, C. (2014). The dorsal medial prefrontal (anterior cingulate) cortex–amygdala aversive amplification circuit in unmedicated generalised and social anxiety disorders: an observational study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(4), 294–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(14)70305-0

Bar-Haim, Y., Lamy, D., Pergamin, L., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2007). Threat-related attentional bias in anxious children: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35(5), 745-757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9125-9

Eysenck, M. W., Derakshan, N., Santos, R., & Calvo, M. G. (2007). Anxiety and cognitive performance: attentional control theory. Emotion, 7(2), 336-353. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.336

Mathews, A., & Mackintosh, B. (2000). A cognitive model of selective attention in anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24(6), 563-576. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005587318774

Hackmann, A., Clark, D. M., & McManus, F. (2000). Recurrent images and early memories in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(6), 601–610. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00161-8

Holmes, E. A., & Mathews, A. (2010). Mental imagery in emotion and emotional disorders. Clinical psychology review, 30(3), 349–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.001

Comments